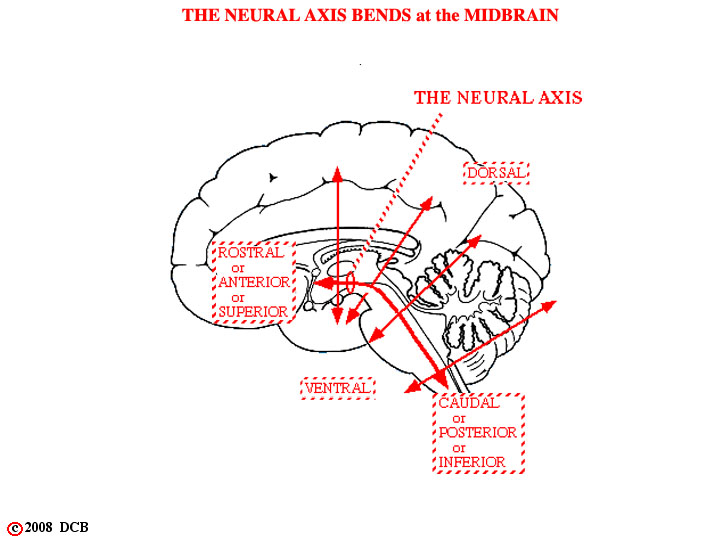

FIGURE 2-17

The neural axis may be pictured as a line which runs along the length of the neural tube and it is indicated by a red line this view. Directional terms use this axis as a reference and are summarized on this view. In general, these words have meanings which are already familiar to you from Gross Anatomy, but there is one exception. In describing the brain, the terms anterior and posterior are the equivalent of rostral and caudal (whereas in the body they are synonymous with ventral and dorsal).

The neural axis is a relatively straight line in four-legged creatures, but in humans it has a definite bend , with most of the bending taking place at the level of the midbrain . This is even more apparent when one looks at views of the developing brain. This bending of the neural axis creates one minor problem and one major one.

1) The direction, specified by such terms as ventral and dorsal, changes in an absolute sense, as one passes from one division of the brain to another. Clearly, the ventral-dorsal plane of the medulla in man is not parallel to the ventral-dorsal plane of the diencephalon. This is a bit odd, but causes no real difficulty.

2) In serial sections of the brain, such as the ones we will be using, it is impossible to alter the angle of section as the microtome knife advances from one region of the brain to the next. If a brain is cut in such a way as to obtain true cross sections (plane perpendicular to the neural axis) through the medulla, then the sections through the diencephalon will be almost horizontal (plane parallel to the neural axis). The sections between these limits will pass through the brain at an oblique angle and be extremely difficult to interpret. This does create a problem and the various published atlases of the brain all try to deal with it--most of them doing so in a rather unsatisfactory manner. The plane of section for slides that we will be using, almost exclusively, in studying the brainstem is shown in the next view.